The Image of the Republican Woman

CIVIL WAR POSTERS

![Crónica: revista de la semana, n.º 365, 8 de noviembre de 1936. Madrid: Prensa Gráfica, [1929-1939]. Fondos del Centro de Documentación del MNCARS Crónica: revista de la semana, n.º 365, 8 de noviembre de 1936. Madrid: Prensa Gráfica, [1929-1939]. Fondos del Centro de Documentación del MNCARS](https://recursos.museoreinasofia.es/microsite/especial/sites/default/files/coleccion/mujeres-guerra-civil/bloque-iii/cronica_n.o_365_8-11-1936_contra.png)

Crónica: Weekly Magazine, No. 365, 8 November 1936. Prensa Gráfica, (1929-1939). Holdings from the MNCARS Documentation Centre

The sheer number of posters made from the Republican zone is striking. By and large, they were produced in centres from Barcelona, Madrid and Valencia, cities with a strong tradition and places from which around 3,500 posters were printed in 986 days of war, an unprecedented historical and graphic-art landmark in Europe.

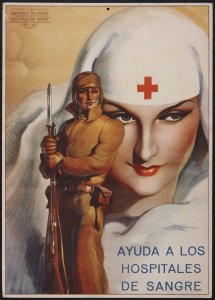

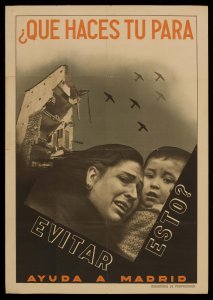

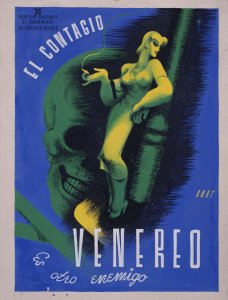

These profuse and varied Republican political posters built a combative iconography that still endures today through their unrelenting validity. An analysis of the posters conserved illustrates the role of graphic arts in constructing the image of the Republican woman and their deployment by the established powers within collective war imagery; however, in most cases, these women were mere spectators in the construction of their image.

The posters displayed on this microsite are, as a whole, devoted to the Republican woman across three years of struggle. They were largely promoted by organisations detached from feminist tenets and, to a large degree, perpetuated secular roles, despite the notable Republican advances achieved in this area. It is also worth noting how women-related issues generally remained at the top of the agenda in parties’ programmes and Spanish revolutionary organisations.

Women Poster Artists

In view of the number of posters with a recognised authorship and designed by men during the Civil War, we find a meagre number made by women artists, while those produced from the Free Women organisation, with a markedly feminist conception, are also a minority.

![Crónica: revista de la semana, n.º 365, 8 de noviembre de 1936. Madrid: Prensa Gráfica, [1929-1939]. Fondos del Centro de Documentación del MNCARS Crónica: revista de la semana, n.º 365, 8 de noviembre de 1936. Madrid: Prensa Gráfica, [1929-1939]. Fondos del Centro de Documentación del MNCARS](https://recursos.museoreinasofia.es/microsite/especial/sites/default/files/coleccion/mujeres-guerra-civil/bloque-iii/aj-0013_0.jpg)

Aurelio Pérez Rioja, male and female students at the School of Fine Arts in the workshop executing propaganda originals in defence of Spanish Art Treasures, 22 June 1936. Committee of Spanish Art Treasures Archive. Spanish Institute of Cultural Heritage

Nevertheless, today a broad number of these posters are identified as anonymous and it would not be beyond the bounds of possibility to think that women artists were behind their authorship. For instance, within the collectives fighting to defend artistic heritage during the conflict we find the committed endeavours of young women who belonged to the University School Federation (FUE) and female students from Fine Arts schools, collectives who worked to support the propaganda efforts of the Committee to Repossess, Protect and Safeguard Artistic Treasures, which, by producing multiple posters aimed at public opinion, sought to protect artworks and avoid their plundering and vandalization.

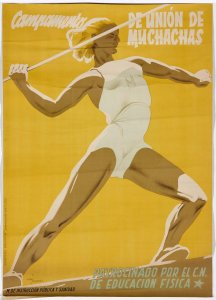

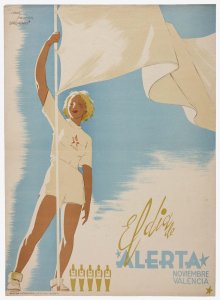

Among the few women poster artists we know of with any certainty during the war was Juana Francisca Rubio (Madrid, 1911–2008), who with her husband José Bardasano (Madrid, 1910–1979) signed posters such as 10*25 Novembre, tota la joventut per la campanya d’hivern and The Day of Alert, November, Valencia. In the latter we see the iconic image of the “new woman” from a Soviet conception: the manifestation of a sole image, a sign of emancipation and liberation from the burden of the past; the woman capable of transfiguring and modelling her body and mind through sport and culture. This new image would become more monumental on the posters of sports camps in the Madrid-based Union of Girls, in which a copybook female, indebted to the influences of the Soviet poster, and just like men, becomes part of sport’s physical activity. It is worth highlighting that these images, at the onset of war, worked to identify women with the image of the revolution.

In Catalonia, the figure of designer Carme Millà Tersol (Barcelona, 1907–1999) shone bright. In July 1936, she edited the Statutes of the New Unified School Council (CENU), and from May 1937 served as a professor of art with the Catalonia Autonomous Government. She is best known for the poster Escola nova, poble lliure (New School: Free People), designed for CENU, in which, through the gratifying representation of a boy and a girl reading together, it defended the Republican model of a secular and co-educational school. Moreover, Millá stood out in her political commitment as founder of Secció de Dibuixants, Pintors i Escultors del Sindicat Únic de Professions Liberals of CNT-AIT in Barcelona; yet, despite playing a key role in these groups of professional visual artists, the designs attributed to her in this period today are noticeably scant and raise multiple questions with respect to the limited graphic-art testimonies of these professional women during the conflict.

Most notably, within the set of works made by women artists, theatre illustrations, fashion advertising and children’s illustrations were the reserved strongholds — mostly by obligation — of these talented female graphic designers. More specifically, during the war children’s illustrations were the sphere in which artists such as Lola Anglada i Sarriera (Barcelona, 1892 – Tiana, 1984) and Francis Bartolozzi (“Pitti”) (Madrid, 1908 – Pamplona, 2004) operated, producing, to promote the children’s weekly publication Sidrín, an eye-catching poster in the form of an auca (rhyming couplet).

Notable from the same illustration context is Enlist in the Militias from Aragón, by Alma Tapia Bolívar (San Lorenzo de El Escorial, 1906 – Mexico, 1993). The poster depicts, in a way that is both kind and forceful, the emphatic and monumental anatomy of a militiawoman at ease: a hard-to-balance synthesis between socialist-style realism and the profession of a children’s illustrator.

Among the narrow group of women graphic artists of which there is a record as poster artists, the youngest is Mariona Lluch (Barcelona, 1927), who aged just nine designed the posters Homenatge a la 43 divisió and Tovaris, Setmanari infantil, a glimpse into the attributes of a children’s illustrator she would develop over the rest of her career.

Therefore, women’s presence in Republican poster art conclusively remains an open line of investigation. A vast number of anonymous posters may surprise us in the coming years and their study is a debt society owes to women’s visual-art contributions in this genre. A survey of the presence of women artist’s in the Museo Reina Sofía’s collection of Civil War posters underlines how of the 91 Republican posters conserved, only six are designed by women, while in 11 the image of women takes centre stage. As a result, the Museo is progressively attempting to redress this deficit, assembling rooms in the Collection like Front and Rearguard: Women in the Civil War.

Inmaculada Julián: The Graphic Representation of Women (1936–1938)

Spain’s Transition to democracy brought with it a definitive drive to study and evaluate posters from the Civil War. The “unofficial” participation of Spain in the 1976 Venice Biennale, devoted to anti-Franco resistance in Spain, demonstrated the historical-artistic value of Republican poster art. Art historian Inmaculada Julián (Barcelona, 1941) was involved in the selection of war posters displayed in Venice as a pioneer in the study of this subject matter, presenting, in 1978, her PhD thesis: The Republican Poster During the Spanish Civil War, with a Focus on Catalonia. Julián’s overall contribution to the study of these posters, and particularly the study of the images of women they bear, are regarded as a reference point in analysing the different archetypes represented on such posters. As a summary of her study, below is her text (in Spanish) “The Graphic Representation of Women (1936–1938)”[1], an analysis of women’s iconology during the Civil War and one which established classifications that have served as a frame of reference for subsequent related studies.