Women and Politics

THE ROAD TOWARDS FULL CITIZENSHIP

Women and the Vote

A feminist symbol since the first suffragettes’ protest actions, the vote for women has been one of the most heavily debated political rights. In the General Elections of 28 June 1931, women were still unable to vote but could be elected as congresswomen by the Decree of 8 May ratifying passive suffrage. The approval of women’s suffrage was attained in Congress during the parliamentary session of 1 October 1931 by virtue of the interventions of Clara Campoamor, opposing even her own political party. Although a large majority of MPs recognised the right of all women to vote in elections, many believed it was not yet the time to grant it, fearing that parties on the Left would be harmed — such was the stance upheld by Victoria Kent and Margarita Nelken, two other representatives in this same term in office. The Constituent Assembly would ultimately approve universal suffrage, reflected in Article 36 of the 1931 Spanish Constitution, and Spanish women could vote for the first time in the legislative elections of 19 November 1933, where the Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Rights (CEDA) gained a majority; and for a second time on 16 February 1936 following the victory of the Popular Front, a coalition of left-wing political parties.

Official Journal of the Constituent Assembly, the Legislature of 1931–1933, No. 48, 1 October 1931. Courtesy of Spain’s Congress of Deputies. Archive Department

Josefina Carabias, "Women, Go and Vote!", Estampa: The Graphic Art and Literary Magazine on Current Affairs in Spain and Worldwide, No. 276, 22 April 1933 (cover and report). Madrid: Suc. de Rivadeneyra, 1928–(1938?), (photographs by Saus, Amado and Cacho). Holdings from the MNCARS Documentation Centre

Access to Politics

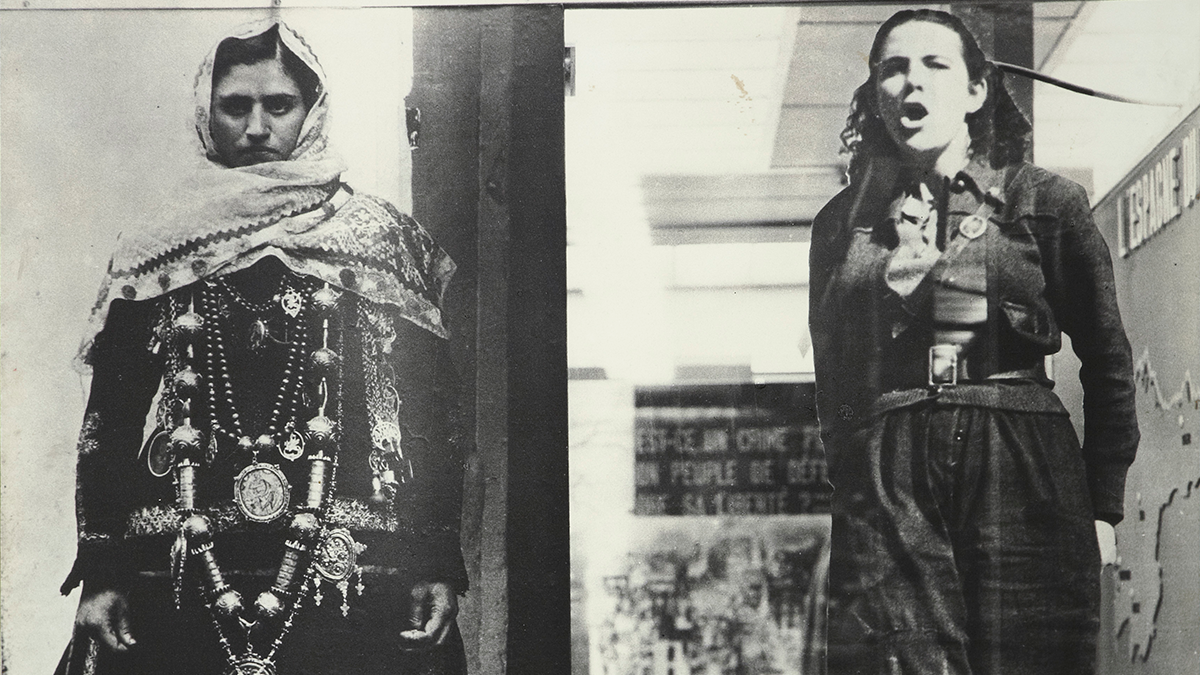

After the approval of passive suffrage, nine women representatives were elected across the three terms of the Second Republic, most notably Clara Campoamor, Victoria Kent, Margarita Nelken, Matilde de la Torre, María Lejárraga and Dolores Ibárruri. During the Civil War years, some female politicians earned greater renown and visibility, for instance Federica Montseny, who headed the Ministry of Health in the government presided over by Largo Caballero, or Dolores Ibárruri, Pasionaria (Passion Flower), a mythical figure as a laic mater dolorosa (lady of sorrows), consistent with her speeches and writing in which there were recurrent references to mothers as suffering heroines. Both Ibárruri and Montseny concentrated their efforts into the general anti-fascist struggle but without having a significant bearing on specific issues related to women, whereas Margarita Nelken, an elected representative in all three terms, published her analyses of the political and social situation, foregrounding women’s plight in titles such as The Social Status of Women in Spain (1919) and Women Before the Constituent Assembly (1931).

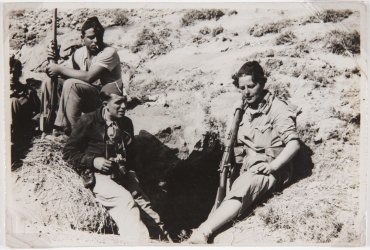

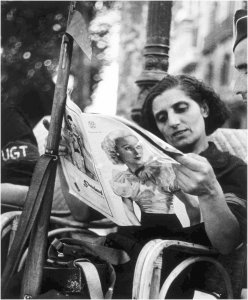

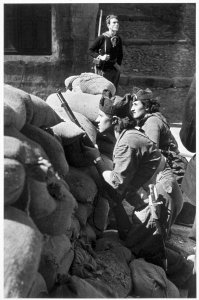

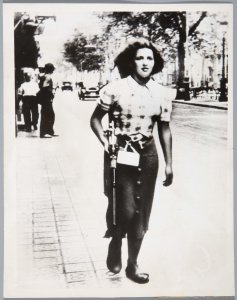

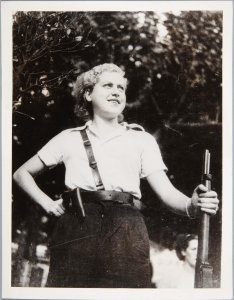

Militiawomen

The early months of the Civil War witnessed a sweeping mobilisation of women determined to participate in armed combat to defend the Republic, with many affiliated with and members of political parties and workers’ organisations. To begin with, the figure of the militiawoman became a symbol of bravery and heroism and was illustrated on myriad Republican posters and magazine covers, in contrast to the caricatures and parodies published by the Nationalist faction, which used them to ignite a smear campaign. Even more consequential and contradictory was the mistrust towards militiawomen at the heart of the Republican faction, which fanned the flames of unfounded fear over the spread of venereal diseases among soldiers. In the autumn of 1936, the Republican Government decreed the requirements for establishing the Popular Army and banned the presence of women among the militias, the point at which the new slogan “Men on the Front, Women in the Rearguard” was adopted by every women’s organisation.

Access to Work

On the road to women’s emancipation there was unanimous agreement regarding the importance of investing in equal education for men and women and training for women so they could access work. Pilar Grangel was a teacher who insisted on the need to reform women’s education, and without distinguishing between class or profession in order for them to fulfil their duty to work. One example of an implemented initiative was Casal de la Dona Treballadora (House of Working Women), where free classes on literacy, professional training and social education were offered.

During the Civil War, the possibilities for women to access positions in factories and workshops grew in number and, via women’s associations such as Mujeres Libres (Free Women), work was vindicated as a right and there was a rebuttal of it being limited to something of a temporary nature due to the armed conflict and the resulting need to replace the positions of mobilised workers.

The 1931 Spanish Constitution recognised labour rights without gender distinctions “save for incompatibilities that the laws indicate” but full equality would not come to pass — to highlight one example, in 1919 Margarita Nelken called out wage inequality suffered by female workers, yet still in 1937 the main women’s associations continued to point to the same discrimination.

A.M. Sol (Mauricio A. Sollín), Woman and War, 1937. Film of the People. PCE (Spanish Communist Party) Archive

Prostitution

The debate over the abolition of prostitution had already been addressed in the 1931 Constitute Assembly sessions, but was ultimately not stipulated in the Spanish Constitution due to a preference over measures to abolish it gradually. In the Civil War years, a change of tack occurred in relation to the issue: after years of stigma and persecution surrounding prostitutes, owing to a consideration rooted in social hygiene and a concern with venereal disease, women’s organisations concentrated their efforts on protecting women with no choice but to operate as sex workers. From this new focal point, the liberatorios de prostitución (prostitution liberation homes) initiatives were put into effect and constituted centres offering the chance to welcome and train women who wanted to move into other professions. Behind this initiative was Amparo Poch y Gascón, a doctor and prolific activist who was named Social Assistance advisor by Federica Montseny. In 1937, Montseny explained her stance in relation to prostitution in her lecture “My Experience in the Ministry of Health and Social Assistance”, and, in consonance with that voiced in different anarchist magazines like La Revista Blanca and Estudios, Montseny felt that profound changes must occur in society, not only morally but also economically and socially, to resolve the issue irrevocably. This debate around prostitution was taken up again during feminism’s second wave and is still pertinent today.

Sexuality and Family

The sway of religious tradition in Spain meant issues related to sexuality remained taboo. However, there were initiatives such as the First Spanish Eugenic Sessions (1933) or publications from the publishing houses Orto and Estudios which made room for debates around ideas of sexual freedom and reproductive issues through so-called maternity awareness. Young Hildegart, a pseudonym of Carmen Rodríguez Carballeira and an illustrious figure, played an active role in disseminating reformist stances on sexual education and birth control, publishing a broad array of articles and monographs, most notably Educación sexual (Sex Education, 1931) and Paternidad voluntaria: profilaxis anticoncepcional (Voluntary Paternity: Contraceptive Prophylaxis, 1931).

Some of the Republican Laws advocating advances in the sphere of civil and social rights were the Divorce Law of 2 March 1932, the Civil Marriage Law of 28 June 1932 and the Artificial Termination of Pregnancy Decree of 25 December 1936, from the Autonomous Government of Catalonia, the last of these an issue in which doctor Félix Martí Ibáñez was a key figure. Despite the legislation on abortion seeking to regulate an already existing practice, its implementation was hindered by a terrain that lacked sufficient preparation. This discrepancy between legal initiatives and social reality was conspicuous in many spheres and negatively affected the attainment of full equality for women.

Related works

![Angelina Díaz, "Equal Work, Equal Salary", Treball magazine, 30 January 1938. Barcelona: Partit Socialista Unificat de Catalunya (PSUC), [1936-1993]. Image courtesy of Arxiu Treball Angelina Díaz, "Equal Work, Equal Salary", Treball magazine, 30 January 1938. Barcelona: Partit Socialista Unificat de Catalunya (PSUC), [1936-1993]. Image courtesy of Arxiu Treball](https://recursos.museoreinasofia.es/microsite/especial/sites/default/files/styles/especial_pagina_mosaico_normal/public/paragraphs/mosaico_imagenes/trabajo_92abc.png?itok=HqMF4u4F)