-

April 28, 2016

Rafael Gil. El hombre que se quiso matar (The Man Who Wanted to Kill Himself)

1942, original version, b/w, 93´

With a presentation by María Dolores Jiménez-Blanco, the curator of Campo Cerrado. Spanish Art 1939–1953 and professor of Art History at the Complutense University of Madrid.

In this film bitterness and critique seeps through the social fabric of comedy without hesitation, establishing an initial symbiosis of realism, costumbrismo and fantasy that would characterise a large part of post-war film texts.

Freed from social conventions after publicly deciding to commit suicide, Federico Solá, a young and brilliant architect without a future, becomes a danger and a source of irritation to the social fabric, comprising a journalist, an entrepreneur, a shopkeeper and an bourgeois loafer, who all come together as they anxiously await the consummation of the final promise. The afflictions of an isolated country in moral and economic collapse is, time and again, laid bare and exploited with the construction of this uncontrollable character which nothing can deny, and through dialogues – halfway between a one-act farce and the grotesque - that help to understand the masterly consideration of Wenceslao Fernández Flórez, the author of the novel which inspired the film, by the comedians of La Codorniz.

-

April 29, 2016

Carlos Arévalo

Ya viene el cortejo… (Here Comes the Parade…) 1939, original version, b/w, 11´

Rojo y negro (Red and Black), 1942, original version, b/w, 80´

The joint screening of both films affords a glimpse into the difficulties facing the new Regime in mobilising propaganda cinema, due to both the different ideological trends behind the military uprising and the syncretic and contradictory sources of Spanish fascism.

Ya viene el cortejo… shows the 1939 Victory March as it searches for its roots in the historical and iconographical motifs that seek to become immemorial. The film sets out to explain how the perfect and triumphant military formations in the march – seen in high-angle avant-garde shots – reach their fullest sense with fades back to an eternal past of medieval castles, cathedrals, religious symbols, and stereotypes of women wearing regional Spanish garments.

Rojo y negro, on the other hand, maintains Carlos Arévalo’s extreme experimental volition. Lost for over forty years and turned into an example of formal radicalism by historiography, the film bears witness to the extraordinary density of a genuinely Falangist work, whose visual findings and extreme formal avant-gardism see it become a kind of cinema substantiated by certain revolutionary sectors inside the Falange, before its ultimate domestication by the Regime. Written and directed by Arévalo, the film deploys dialectic and visual mechanisms of Eisenstein’s intellectual montage, even incorporating images from Battleship Potemkin (1925) to give filmic shape to the “need” for revolt.

-

May 5, 2016

Edgar Neville

Verbena (Madrid Carnival), 1941, original version, b/w, 30´

La torre de los siete jorobados (The Tower of the Seven Hunchbacks), 1944, original version, b/w, 99´

With a presentation by José Luis Castro de Paz, curator of the series and professor of Audiovisual Communication at the University of Santiago de Compostela.

The work of Edgar Neville, perhaps the most important film-maker from this decade, adopted a process which appropriated elements of popular culture in Spain, reformulating them into a new mode of expression. The joint screening of Verbena (1941) and La torre de los siete jorobados (1944) notes how minor popular forms, the serialised novel, the police novel, purist costumbrismo, and the one-act farce, with direct allusions to avant-garde movements, co-exist in these films.

Verbena, produced within a series of small cinematic dramatizations inspired by popular songs, describes a dark and touching microcosm comprising the anomalous alliance between the working classes and eccentric artists from circus. The other screening, La torre de los siete jorobados, synthesises a purist criminal tale with traits that are directly rooted in German Expressionism. The film combines two opposite worlds: on one side, the nocturnal, fantastical and bizarre, embodied in this inverted underground tower inhabited by deranged sages, dwarfs and hunchbacks exiled from the light. And on the other, the costumbrista and comic sketch from Madrid, much-loved by the film-maker; this time set in the last third of the 19th century.

-

May 6, 2016

Ignacio F. Iquino. Los ladrones somos gente honrada (We Thieves Are Honourable)

1943, original version, b/w, 102´

This film constitutes a paradigmatic example of the paradoxical and reflexive trend cultivated in the first post-war period and emerging from the complex melange between film and comical and visual resources stemming from absurd and avant-garde humour. With filmic precedents already in the Republican period, the model reached its definitive formulation at a time that coincided with the appearance of the renowned humorous magazine La Codorniz.

Deliberately artful and farcical, Los ladrones somos gente honrada is a parody of the plausibility of classical cinema as it breaches each of its norms. Everything operates in double meanings, paradox, antithesis and two faces that are entangled to fever pitch - “this house is a film”, one of the characters even utters. In a meandering and scattered way, the film pulls us out as viewers and drops us into the scene, or, similarly, dismantles the transparency of orthodox narrative to benefit our strengthened role as participants in an artificial and distant event.

-

May 12, 2016

Arturo Ruiz-Castillo. Las inquietudes de Shanti Andía (The Restlessness of Shanti Andía)

1946, original version, b/w, 121´

A collaborator of Federico García Lorca in La Barraca, art director of the publishing house Biblioteca Nueva and cultural spokesperson during the Republic, Arturo Ruiz-Castillo already had vast experience as a documentary-maker before debuting as a feature-film director with the adaptation of Las inquietudes de Shanti Andía (1946).

The film displays eye-catching discursive and formal strategies (narratological rigour, the deployment of the storyline in independent sequences that match the character’s psychological development, ornamental and compositional symbolism, inter-textual traits…) which bear witness to the artistic ambition of a director encompassed in the generation of “reformist” film-makers who, with vivid and bold aesthetic preoccupations, made their debut in the second half of the first decade under the France regime. Audaciously using Pío Baroja’s novel to discuss the present, the film turns oedipal conflicts and anxieties of desire into effective narrative copies of an unlivable time.

-

May 13, 2016

Carlos Serrano de Osma. Embrujo (The Spell)

1947, original version, b/w, 80´

Carlos Serrano de Osma is the visible leading figure in the self-styled “telluric” cinema, an informal circle of friends brought together around the magazine Cine experimental (1944–1946). A film-maker of enunciation and point of view, his films from this period incorporate the European legacy of Eisenstein and Pabst, and the American legacy of Welles, Siodmak and, above all, Hitchcock in a dense corpus of literary references and iconographic, autochthonous references, creating a poetic narrative style strongly imprinted with psychoanalysis.

Embrujo manages to – in the film-maker’s declared intention – “reach the shadows of the unconscious through the brilliant routes of folklore.” The film, a musical drama that is explicitly surreal, heart-rending and a moving reflection on desire and delirious passion, pieces together a highly risky operation in the film industry: combining the popular and the avant-garde, using the former as a cushion for the second.

-

May 19, 2016

Lorenzo Llobet-Gràcia. Vida en sombras (Life in the Shadows)

1948, original version, b/w, 90´

Punished to the point of ostracism by the censorship that would classify it as “inconceivable, unacceptable, inadmissible and disgraceful”, Vida en sombras is perforated by the trauma of the Civil War, which fights to make itself present. The beginnings of the conflict are narrated from the Republican side: news fragments from the time and a speech in Catalan by the president Companys are heard on the radio. In this milieu, the loss of the object of desire, embodied by the character Ana, who dies in the first skirmishes on the Barcelona streets, is bound up with unique force; thus tracing the stark identification between the harsh post-war period and the loss and scarring of the subject.

War, death, the incurable wound of desire: upon these three pillars, inextricably linked by the mise en scène, the film articulate its strategies of meaning. And further still, in a new, all-engulfing circle, cinema appears as a place where the subject’s desire (film-maker, protagonist, viewer) is radically affected.

-

May 20, 2016

Rafael Gil. La calle sin sol (The Sunless Street)

1948, original version, b/w, 95´

In an audacious mix of film noir, veristic will, and a costumbrista background, this distinctive thriller joins a series of obsessive and dense post-war films with sharp psychoanalytical resonances. Set in the desolate and poverty-stricken night-time of Barcelona’s Chinatown, inhabited by long-suffering survivors without hope, the story delves into dark crimes and destroyed families, and stresses the recreation of lumpen settings in the Catalan capital, depicted as a place of prostitution and illegal trade, where the residents represent at once the danger of extortion and the possibility of help. What ultimately emerges, via the film’s formal density, is a textual fabric torn at its seams, and understood as a symptom of the unconscious repression in the ruling classes in the face of social decomposition and rotting morals after the war.

-

May 26, 2016

Juan de Orduña. Locura de amor (Madness for Love)

1948, original version, b/w, 112´

The historical works directed by Juan de Orduña are the most original, complex and contradictory confluence of ideological interests from the Regime, from the eagerness for pomp and majesty from the producer CIFESA and from the tastes of the actual spectators. Locura de amor would constitute the greatest audience success of the season and one of the greatest in this decade; the “Spanishness” of these sorts of films was favoured by a large number of critics who saw in the historical literary, and not folkloric, adaptation a place in which film would have to redefine itself. The reasons for its undeniable popular allure were in its markedly melodramatic volition, characterised by the prominence of the suffering female figure. Built as a monumental and literal succession of living paintings, Locura de amor seeks to breathe life, not into events in History with a capital H but into the signs that have gone some way to building a romantic and timeless legend of the love story of Juana la Loca and Felipe el Hermoso.

-

May 27, 2016

José Antonio Nieves Conde. Surcos (Furrows)

1951, original version, b/w, 99´

The direct appearance of questions related to a lack of housing, unemployment, prostitution and rural exodus, in addition to the direct relationship with models of film such as Italian Neo-realism, define the exceptional nature of Surcos, both in this decade and generally throughout the history of Spanish cinema. The film’s emotional tension places it in the orbit of the film seasons that narrate the vicissitudes of a group of characters in a hostile environment, in an occupied country, a besieged city, an idea that manifests itself through the reiterated visual motif of furrows (prison bars, farmyard steps, an open grave, a ploughed field). On one side, claustrophobic confinement in small, shared spaces that are overpopulated or inhospitable; and on the other, an urban prison in which one cannot settle, feel at home and rest. Each sequence is structured through an exit or arrival, repeating the transition to nowhere that underpins the film to the grave, the final furrow.

Life in the Shadows. Spanish Cinema in a Labyrinth (1939–1953)

Held on 28, 29 Apr, 05, 06, 12, 13, 19, 20, 26, 27 May 2016

This film series, organised in conjunction with the exhibition Campo Cerrado. Spanish Art 1939–1953, focuses on post-war Spanish cinema, moving beyond the clichés that have buried it for a number of decades to present a dark yet fascinating filmic and historical labyrinth displaying conflicts, searches and objectives from the main narratives in a melancholic period, wounded and confrontational period.

The dictatorial regime organised film production in a diametrical opposite to the Republican period as it developed a system of economic autarchy and staunch ideological censorship. Nevertheless, contrary to widespread assertions, it also searched for continuity in the cultural traditions that had been put in place during the Second Republic. The new State failed, however, in its aim to construct “fascist” cinema on account of the disparity of conflicting views, thus demonstrated in the differences between long-standing conservatism in Raza (Race), by José Luis Sáenz de Heredia (1942), and the Falangist and Eisensteinian modernity of Rojo y negro (Red and Black), by Carlos Arévalo (1942). It would also err in its attempts to remove the folkloric and popular substrata which, despite fierce opposition by those who saw such elements as an abominable Popular Front-esque inheritance, managed to remain and was depicted in the work of director Edgar Neville - a pragmatic and measured cultural opposition with authentic and subversive titles like Verbena (Madrid Carnival, 1941), La torre de los siete jorobados (The Tower of the Seven Hunchbacks, 1944) and the Solanesque Domingo de carnaval (Carnival Sunday, 1945).

Despite the darkness of the period, comedy would become the most common genre. Drawing influences from the modern and absurd humour found in the magazine La Codorniz (founded in 1941 by Miguel Mihura), this decade’s filmography was predominated by a decidedly reflexive and meta-cinematic volition, expounding the difficulty facing fiction when it came to addressing the dark reality that had begun after the Civil War.

Dissidents in their own way, the films by the so-called “reformists” (Jose Antonio Nieves Conde, director of the transcendental Surcos (Furrows) in 1951; Arturo Ruiz-Castillo and Manuel Mur Oti) and the “tellurics” (Carlos Serrano de Osma, Lorenzo Llobet-Gràcia y Enrique Gómez), demonstrated a pronounced social concern and a striking “aesthetic commitment” – with European and avant-garde roots yet also strongly influenced by Hollywood – in addition to profound psychoanalytical concerns, conveying harrowing discourses about the life and times and the destructive consequences.

The irreparable loss of the loved object, often portrayed by a murdered, forbidden or missing woman, the ensuing melancholy and even madness and the narrative junctions that were customarily employed at the time can be read as metaphors of a devastated country, inhabited by sombre memories which carried an uncontrollable guilt complex. Thus, sadness, destruction and historical solitude became lucid “wounds of desire”.

Curatorship

José Luis Castro de Paz

Acknowledgments

Filmoteca Española

Más actividades

![Tracey Rose, The Black Sun Black Star and Moon [La luna estrella negro y negro sol], 2014.](https://recursos.museoreinasofia.es/styles/small_landscape/public/Obra/AD07091_2.jpg.webp)

On Black Study: Towards a Black Poethics of Contamination

Monday 27, Tuesday 28 and Wednesday 29 of April, 2026 – 16:00 h

The seminar On Black Study: Towards a Black Poethics of Contamination proposes Black Study as a critical and methodological practice that has emerged in and against racial capitalism, colonial modernity and institutional capture. Framed through what the invited researcher and practitioner Ishy Pryce-Parchment terms a Black poethics of contamination, the seminar considers what it might mean to think Blackness (and therefore Black Study) as contagious, diffuse and spreadable matter. To do so, it enacts a constellation of diasporic methodologies and black aesthetic practices that harbor “contamination” -ideas that travel through texts, geographies, bodies and histories- as a method and as a condition.

If Blackness enters Western modernity from the position of the Middle Passage and its afterlives, it also names a condition from which alternative modes of being, knowing and relating are continually forged. From within this errant boundarylessness, Black creative-intellectual practice unfolds as what might be called a history of touches: transmissions, residues and socialities that unsettle the fantasy of pure or self-contained knowledge.

Situated within Black radical aesthetics, Black feminist theory and diasporic poetics, the seminar traces a genealogy of Black Study not as an object of analysis but as methodological propositions that continue to shape contemporary aesthetic and political life. Against mastery as the horizon of study, the group shifts attention from what we know to how we know. It foregrounds creative Black methodological practices—fahima ife’s anindex (via Fred Moten), Katherine McKittrick’s expansive use of the footnote, citation as relational and loving labour, the aesthetics of Black miscellanea, and Christina Sharpe’s practices of annotation—as procedures that disorganise dominant regimes of knowledge. In this sense, Black Study is approached not as a discrete academic field but as a feel for knowing and knowledge: a constellation of insurgent practices—reading, gathering, listening, annotating, refusing, world-making—that operate both within and beyond the university.

The study sessions propose to experiment with form in order to embrace how ‘black people have always used interdisciplinary methodologies to explain, explore, and story the world.’ Through engagements with thinkers and practitioners such as Katherine McKittrick, C.L.R. James, Sylvia Wynter, Christina Sharpe, Fred Moten, Tina Campt, Hilton Als, John Akomfrah, fahima ife and Dionne Brand, we ask: What might it mean to study together, incompletely and without recourse to individuation? How might aesthetic practice function as a poethical intervention in the ongoing work of what Sylvia Wynter calls the practice of doing humanness?

Intergenerationality

Thursday, 9 April 2026 – 5:30pm

This series is organised by equipoMotor, a group of teenagers, young people and older people who have participated in the Museo Reina Sofía’s previous community education projects, and is structured around four themed blocks that pivot on the monstrous.

The third session gazes at film as a place from which to dismantle the idea of one sole history and one sole time. From a decolonial and queer perspective, it explores films which break the straight line of past-present-future, which mix memories, slow progress and leave space for rhythms which customarily make no room for official accounts. Here the images open cracks through which bodies, voices and affects appear, disrupting archive and questioning who narrates, and from where and for whom. The proposal is at once simple and ambitious: use film to imagine other modes of remembering, belonging and projecting futures we have not yet been able to live.

Remedios Zafra

Thursday March 19, 2026 - 19:00 h

The José Luis Brea Chair, dedicated to reflecting on the image and the epistemology of visuality in contemporary culture, opens its program with an inaugural lecture by essayist and thinker Remedios Zafra.

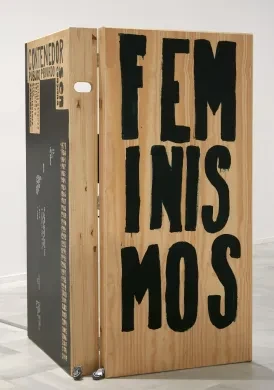

“That the contemporary antifeminist upsurge is constructed as an anti-intellectual drive is no coincidence; the two feed into one another. To advance a reactionary discourse that defends inequality, it is necessary to challenge gender studies and gender-equality policies, but also to devalue the very foundations of knowledge in which these have been most intensely developed over recent decades—while also undermining their institutional support: universities, art and research centers, and academic culture.

Feminism has been deeply linked to the affirmation of the most committed humanist thought. Periods of enlightenment and moments of transition toward more just social forms—sustained by education—have been when feminist demands have emerged most strongly. Awareness and achievements in equality increase when education plays a leading social role; thus, devaluing intellectual work also contributes to harming feminism, and vice versa, insofar as the bond between knowledge and feminism is not only conceptual and historical, but also intimate and political.

Today, antifeminism is used globally as the symbolic adhesive of far-right movements, in parallel with the devaluation of forms of knowledge emerging from the university and from science—mistreated by hoaxes and disinformation on social networks and through the spectacularization of life mediated by screens. These are consequences bound up with the primacy of a scopic value that for some time has been denigrating thought and positioning what is most seen as what is most valuable within the normalized mediation of technology. This inertia coexists with techno-libertarian proclamations that reactivate a patriarchy that uses the resentment of many men as a seductive and cohesive force to preserve and inflame privileges in the new world as techno-scenario.

This lecture will address this epochal context, delving into the synchronicity of these upsurges through an additional parallel between forms of patriarchal domination and techno-labor domination. A parallel in which feminism and intellectual work are both being harmed, while also sending signals that in both lie emancipatory responses to today’s reactionary turns and the neutralization of critique. This consonance would also speak to how the perverse patriarchal basis that turns women into sustainers of their own subordination finds its equivalent in the encouraged self-exploitation of cultural workers; in the legitimation of affective capital and symbolic capital as sufficient forms of payment; in the blurring of boundaries between life and work and in domestic isolation; or in the pressure to please and comply as an extended patriarchal form—today linked to the feigned enthusiasm of precarious workers, but also to technological adulation. In response to possible resistance and intellectual action, patriarchy has associated feminists with a future foretold as unhappy for them, equating “thought and consciousness” with unhappiness—where these have in fact been (and continue to be) levers of autonomy and emancipation.”

— Remedios Zafra

ARCO2045. The Future, for Now

Saturday 7, March 2026 - 9:30pm

The future, its unstable and subjective nature, and its possible scenarios are the conceptual focus of ARCOmadrid 2026. A vision of the future linked to recent memory, a flash of insight into a double-edged sword. This year's edition, as in the previous two, will once again hold its closing party at the Reina Sofia Museum. This time, the star of the show is Carles Congost (Olot, Girona, 1970), one of the artists featured in the new presentation of the Collections recently inaugurated on the 4th floor of the Sabatini Building.

Carles Congost, with his ironic and timeless gaze, is responsible for setting the tone for this imperfect future, with a DJ session accompanied by some of his works in the Cloister on the first floor of the Sabatini Building of the Museo on the night of Saturday 7 March.

27th Contemporary Art Conservation Conference

Wednesday, 4, and Thursday, 5 March 2026

The 27th Contemporary Art Conservation Conference, organised by the Museo Reina Sofía’s Department of Conservation and Restoration, with the sponsorship of the Mapfre Foundation, is held on 4 and 5 March 2026. This international encounter sets out to share and debate experience and research, open new channels of study and reflect on conservation and the professional practice of restorers.

This edition will be held with in-person and online attendance formats, occurring simultaneously, via twenty-minute interventions followed by a five-minute Q&A.