The Construction of the Hospital General

The Start of Building Work

The Sabatini Building was conceived in the eighteenth century as a large hospital that aimed to unify, expand and improve healthcare facilities and premises in the Atocha area of Madrid, for instance those pertaining to the former Hospital General y de la Pasión. The idea for this project in fact dates back to 1566, when Philip II wished to concentrate Madrid’s hospitals and care facilities in the same building. In 1748, in view of the declining state of the aforementioned Hospital General and Hospital de la Pasión, Ferdinand VI proposed the construction, in situ, of a new building, the Hospital General, creating to such ends the Royal Congregation of Hospitals and its governing body, the Board of Royal Hospitales General y de la Pasión. The military architect and engineer José de Hermosilla (Llerena, Badajoz, 1715 – Leganés, Madrid, 1776) was entrusted with the project after an initial proposal by Ventura Rodríguez (Ciempozuelos, Madrid, 1717 – Madrid, 1785) was declined.

From the outset, financial difficulties hindered the progress of the works, leading to certain disagreements and, ultimately, Hermosilla being dismissed in 1769, with Charles II now on the throne, in favour of architect Francesco Sabatini (Palermo, Italy, 1721 – Madrid, 1797). No direct references are preserved from Hermosilla’s plans and work and the details available today largely stem from the mentions, reports and comments of his successor, Sabatini. Based on the scant information available, Hermosilla is attributed with the design of a rectangular ensemble with six courtyards and the start of works on today’s building, specifically in relation to the foundations and the first floor.

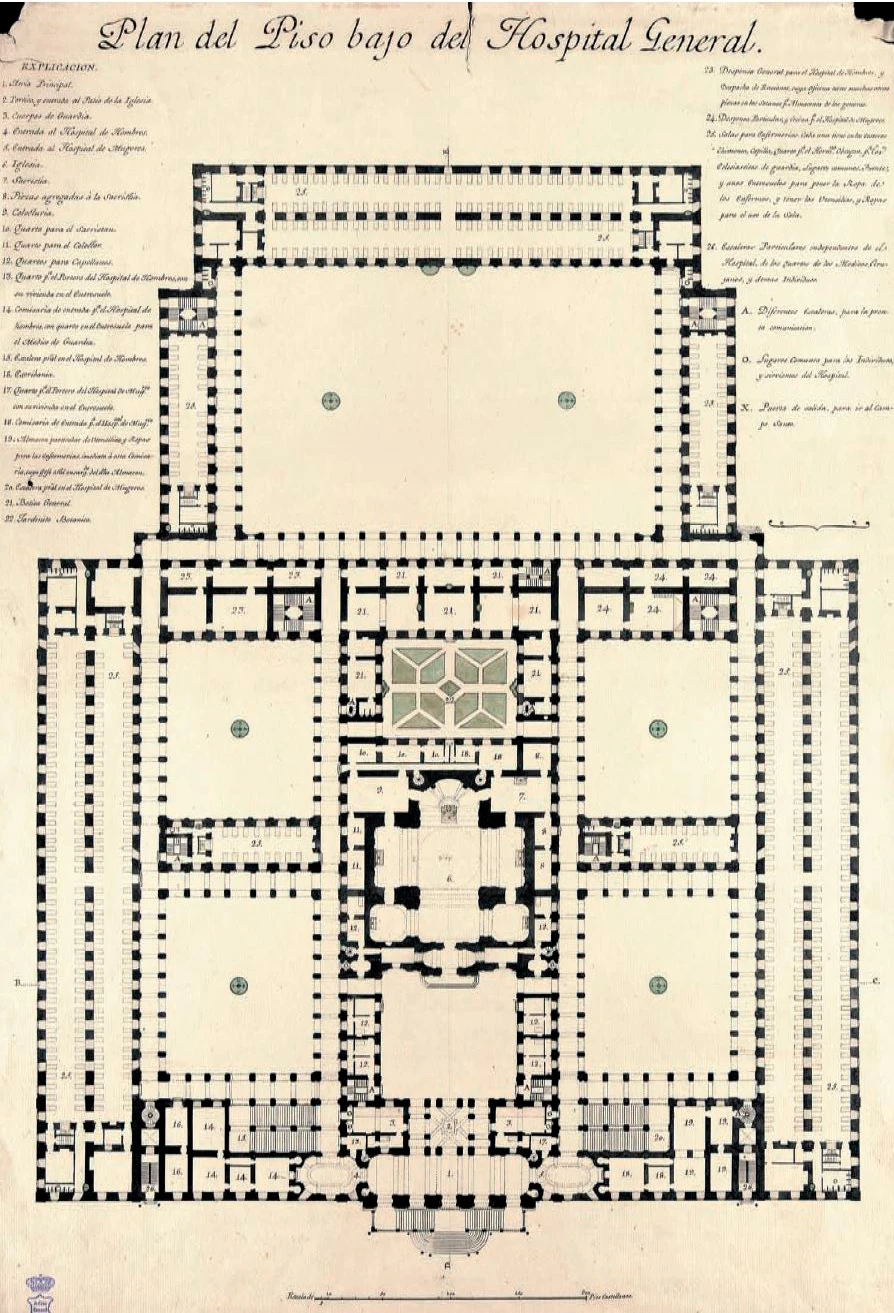

Francesco Sabatini, Plan of the lower floor of the Hospital General

Unfinished Project

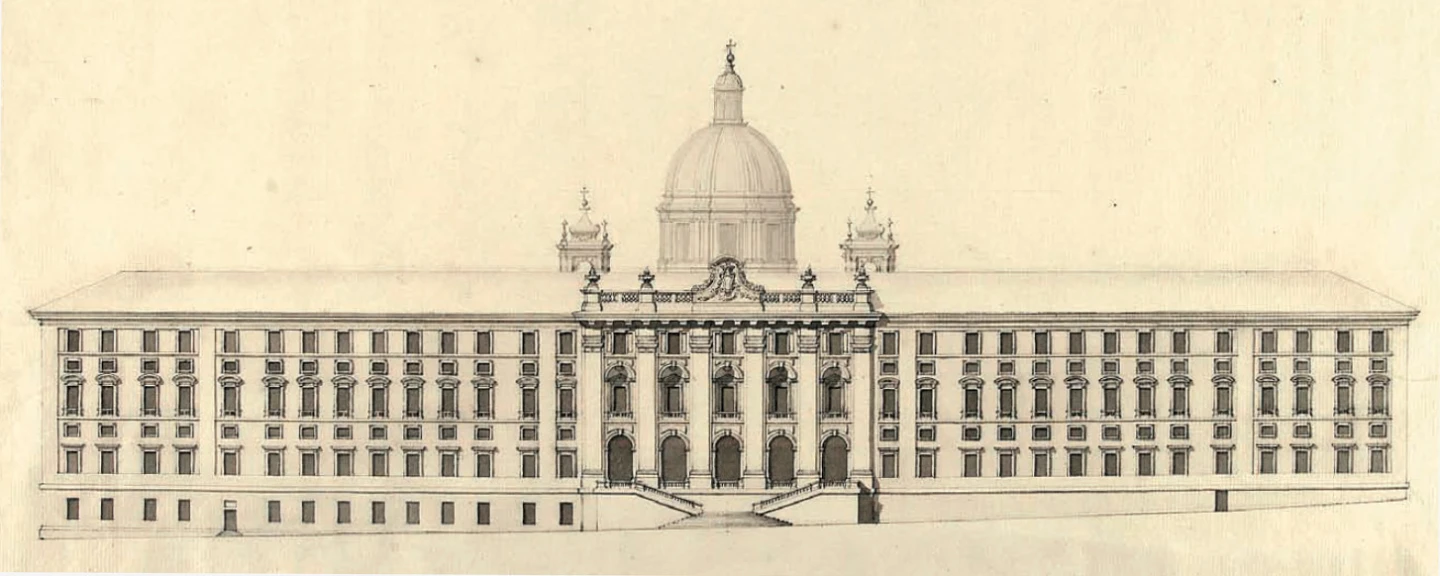

Francesco Sabatini, Main façade of the Hospital General on Calle Atocha

Francesco Sabatini would make a number of changes to Hermosilla’s design for the purposes of lending the architectural complex greater monumentality: he designed a broad main façade facing on to Calle Atocha and arranged the layout of the outbuildings around a domed church with a Greek-cross plan, surrounded by six courtyards, one in the form of an atrium. These were joined by a seventh larger courtyard, rectangular-shaped, located behind the church and also surrounded by a cloister. This courtyard was designed to house two fountains and tree species similar to those in Madrid’s Royal Botanical Gardens, the initial project of which was also by the Italian architect.

Chiming with the ideas illustrated, Sabatini introduced inside the ensemble a series of hygiene and sanitation measures that were ahead of their time: natural cross ventilation, broad spaces with high ceilings, whitewashed walls and the distinction between “server” spaces allocated for healthcare workers and transit areas, and “served” spaces to accommodate the sick.

Following the death of Charles III in 1788 and, once again, given the difficulties in funding the construction, the work ground to a halt at the end of that century — had it been finished at that stage, it would have culminated in the largest healthcare building around. Only a third or so of it was built, however: the seventh courtyard and its cloister, with both fountains — the garden corresponds to a contemporary design — which today form the main site of the Museo; and a free-standing pavilion, which stretches across the arm of one of the courtyards and which today is the site of Madrid’s Royal Conservatory of Music.

Despite the project remaining unfinished, the hospital did fulfil its role for just shy of two centuries, and other renowned architects would also be involved, for instance Juan de Villanueva (Madrid, 1739–1811), who succeeded Sabatini in heading the project following the Italian architect’s death. Subsequent transformations adapted the construction to new hospital requirements and then later, in the twentieth century, to its new role as a museum.